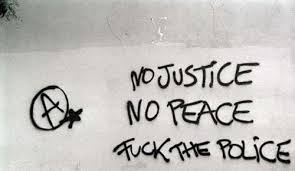

No justice, no peace. This is a phrase that is used often during protests and other political demonstrations, in which the protesters demand that justice be served or else they will continue to disrupt the status-quo. Based off of this mantra, it should lead us to assume that if there is justice, there will be peace. The term justice is used by many groups from all across the political spectrum, but justice is a very subjective term. What is justice to one group may be retribution to another group. Is justice a necessity for peace, or does the framework of justice get in the way of true conflict resolution?

Lets start with a narrative that has been etched into the psyche of of our collective culture in the United States, September 11th, 2001. On that day, more than thirteen years ago, the United States was attacked, and our elected officials agreed that the attacks were carried out by Al Qaida, an extremist Islamic group headquartered at the time in Afghanistan. The people who carried out the attack died along side their victims that day, but the United States wanted justice. We will never forget President George W. Bush standing at the rubble where the twin towers stood, promising the American public that justice would be served. In the weeks and months that followed, the United States set out on its quest for justice, invading Afghanistan and defining a new Global War on Terror (GWOT). The war was accepted as just, and in order for our country to heal there must be justice.

Thirteen years have passed, and our country is still in Afghanistan. The leader of Al Qaida, Osama bin Laden, is dead. Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, is captured. The questions we now have to ask ourselves are, has justice been served? Are we better off as a country? If justice has been served, are we better off? In our quest for justice, we have shifted our paradigm of the conflict from seeking justice, to ensuring that a 9/11 style attack never happens again. The torch has been passed from President Bush to President Obama, as we preemptively seek justice from those who even think of doing us harm. As the GWOT continues, it is clear that we are still engaged in conflict, so there is not yet peace. This begs the question, that if justice was served, why isn’t there peace?

One reason that there might not be peace is because of our desire for justice. In the GWOT, thousands of people, on all sides of the conflict have lost their lives. Families have been torn apart, and people have been displaced. We have expanded our justice quest into Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Somalia, and Pakistan, just to name a few of the countries in which we are engaged in the GWOT. Support for the war has decreased since its inception both here in the United States and around the world. Our list of enemies has increased, and the prospect of peace appears increasingly harder to find. For those who advocate the prolonging of this war, justice must be continuously sought, but at what cost? When does the cost of justice outweigh the benefit? Will the justice sought by the architects of the GWOT ever be achieved?

Over the past few months, we have dealt with calls for justice in a renewed yet ongoing conflict, between our nations law enforcement officers and marginalized communities. We have seen time and time again, cases where the very people who we entrust to protect us, are causing what many believe to be unjust harm. Millions of people across the United States and the world have taken to the streets to demand justice be served to the police officers who they believe murdered unarmed black men. When Darren Wilson, an officer who killed unarmed teen Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Daniel Pantaleo, an officer who killed the unarmed Eric Garner in New York City, were not indicted, it caused many to believe that the system is flawed. In order for justice to be met, the protesters believe that the police officers who killed the men must be indited, and face a trial where they will be judged by a jury of ordinary citizens.

Again, we must ask ourselves if justice is served to the police who kill unarmed black men, is peace achieved? Is peace ever achieved by justice, or does justice serve to prolong the conflict. If justice is served against Wilson and Pantaleo in the way that the protesters see fit, there will undoubtedly be those who believe that inditing our police is an injustice, and they were doing their jobs. We are a society of laws, and there will always be a need for justice, or the threat of justice as a deterrent. Once the cost of seeking justice is no longer cost effective, we must seek other means to resolving the underlying causes of the conflict. If we examine the root causes of the conflict, it will be more cost effective in the long run, as we can rely on the administration of justice less.

After 9/11, we needed to heal, and in a realpolitik world, we must let it be known that there are consequences to attacking the United States. Justice did not help to heal our collective consciousness, but rather served as a deterrent. Now that it has proven to be less of a deterrent than previously thought, its time that we have a real dialogue with those who want to do us harm. Why did they attack us? Was their attack on us their quest for justice? In the cases of Wilson and Pantaleo, did they seek to carry out justice in the way they were taught? Is our justice system at odds with a peaceful society? As with all things in life we must strive to find a balance between justice and peace, but justice should not come at the expense of peace.