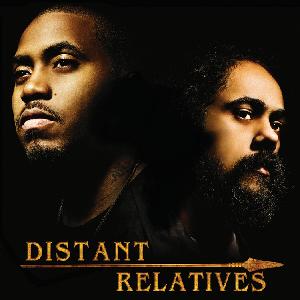

In 2010, a fusion album dropped that would change the way I viewed hip-hop fusion albums, that album was Distant Relatives by Nas and Damian Marley. It was the most innovative mix of rap and reggae that I have ever heard. It is such as perfect fusion of the two genres, that I have a hard time calling it a hip-hop album as it could just as easily be a reggae album with rap verses. For those of you who are not familiar with either artist, Nas is regarded as one of the best rap lyricists of all time, hailing from Queens, New York, where he began recording conscious rap music in 1994. Damian Marley is the son of reggae legend Bob Marley, and brings an uptempo rhythm to reggae music. Damian has won a few Grammy’s for his albums The Halfway Tree and Welcome to Jamrock. Both are artists that are at the top of their field, revolutionizing their genres.

When Distant Relatives came out, it was at a time when people, including Nas, had claimed that hip-hop was dead. That is why I found it so strange that he was able to contribute to an album that proved that hip-hop was not only alive, it was growing in new and exciting ways. From the opening track, As We Enter, it was clear that there would be a back and forth between the two MC’s over bass heavy beats. You could tell that they were speaking as a voice of their respective communities that were so distant in proximity to one another, yet so similar in nuanced ways. It was a party track that got the album off to a fast start, yet really didn’t have the light lyrics to match the uptempo beat.

The next song on the track on the album, Tribal War, had the albums first guest feature from an up and coming Somalian rapper named K’naan. I had actually first learned about K’naan back in 2007 when he opened for Stephen and Damian Marley on the Mind Control tour. The track introduced an African theme that would be present through much of the album. This song spoke about the need for humans to divide ourselves into tribes, and engage in conflict. This song also made the connection of the album title, because we are all distant relatives. K’naan from Somalia, Nas from NY, and Damian from Jamaica can all trace their ancestry to the continent of Africa, which is why the addition of the African beats into the album was a great concept. K’naan makes another appearance at the end of the album on the final track Africa Must Wake Up, which is an uplifting song about how the future is bright for Africa despite some dark days ahead. We hear K’naan spitting some raps in his native language which was pretty cool.

This leads me to one of my favorite track on the album, Patience. Patience uses a sample from the famous Malian duo Amadou and Mariam’s song Sabali. Sabali is the Bambara word for patience. I had heard this song when I first listened to the album, and even though I liked it, it was not an instant favorite. Then I heard Amadou and Mariam’s song when I served in Mali for the Peace Corps, and I was blown away. They used the sample, and did it a lot of justice. The beat was trance like, with Miriams gentle voice echoing on the chorus. This made me pay special attention to the lyrics of the verses, and I began to pick up subtleties that I had not picked up on before.

Another theme on this album is hope, and there were two tracks on Distant Relatives that evoked strong feelings of hope for me. Count Your Blessings is one of the most uplifting songs I can think of, reminding the listener that even when times are tough, you should always be thankful for the things that you do have. The other hopeful song was My Generation, featuring Joss Stone who is a powerful voice in the R&B world, and Lil Wayne, a rapper not known for his political or substantive raps. Both of them added great depth to the song. My Generation also features a chorus of children singing in the background, reminiscent of I Know I Can, on Nas’s God’s Son album. Both tracks put the listener in an uplifting mood, and you can’t help but sing along.

This leads me to my favorite track on the album, Nah Mean, which had the most traditional hip-hop beat on the whole album. What else can I say, other than it sounds great turned all the way up on your system when your driving. Again we see the great chemistry between Nas and Damian as they trade lines on the verses. We see a bit of the gangster persona that both artists have showcased on previous albums. At the same time we are also presented with issues of injustice, as they call out the president and prime minister for not caring about marginalized communities. For those of you who are not familiar with the term Nah Mean, it is basically slang for ‘do you know what I mean’.

Other rappers have tried to do fusion albums with other artists, but they never end up sounding natural. Jay-Z has done it a few times, with R. Kelly for the Best of Both Worlds, as well with Kanye West with their album Watch the Throne. Both of his albums seemed like they were manufactured by some studio executives to sell a ton of records, but really had no substance. Distant Relatives differs so much from Jay’s fusion albums, as every song is substantive. You get the feeling that Nas and Damian are attacking the system, while other rappers are deeply entrenched in the system. From gentrification, to war, to inequality, to hope, and to love, the listener connects with the themes and doesn’t merely feel like an observer, but a participant in the Distant Relatives experience.